A Tale of Finite - Images of Babel

So, I was doing some wondering (in the shower of course) about finiteness, and how powerful something finite could even get. And then I remembered reading something funny about how the display of your monitor is finite — of course it is! It can only display a certain amount of pixels, each pixels having only certain values. And yet. We have access to everything we have access to on here — games, social media, masterpieces of text and film. All of it! And when you think about it some more, I came to a simple realisation that just because something can be counted does not mean it should be scoffed at.

The Library of Babel

You might have heard of it. Gaining inspiration from the Tower of Babel, the library of babel is effectively a library of all possible known texts (up to a limited size, just so it can be calculated). There’s even a website for it! You can go and peruse the library, where there lies all the texts ever written, and that ever will be written, right there. Among the hexagonal sections. Since they’ve already done that, let’s talk about images1.

The Realm of Images

We can imagine a site that just displays random pixels. Let’s say it’s a 1024 x 1024 pixel display. That’s a decent resolution — if there’s any pictures on your phone, you could almost definitely see it in this size. I’ll talk more about what it means later as I’m (unapologetically) going to insert some maths here.

Now, I know 1024x1024 is somewhat large — you can probably see most images in 512 x 512 just fine (without pixel artifacts, and being able to clearly discern the image and its contents), but I’m going to stick with a 1024-sized image for now because who doesn’t want to suffer existential crises with pretty images?

How could we set some order to this mess? It all seems a bit arbitrary right now, and how big is this really? Could we somehow number every possible picture?

Turns out, yes. And it’s pretty simple too!

Babel Numbers

Similar to Godel’s numbers, let’s construct Babel’s numbers (if you want to give me a shoutout, call it Anti’s numbers2 :P — I don’t want to search if this has been done before: I would like to relish in the little glory I can have, thank you. It is a first on my personal timeline!)

Basically, we can describe every possible image in this 1K image display as a simple number — its a unique identifier! Say, a picture of your cat would be 3024244925. We can even describe a video as a sequence of these numbers like: {0, 696932929352, 2112303010, 23020, …}

But how high can these Babel numbers go? We have to understand that, at 1K resolution, you would almost certainly be able to tell what that photo is saying — CCTV footage of a filled mall, a photo of a boat, a cat moments before it falls off a cupboard. You name it, it’s there.

How many Babel Numbers are there?

Spoilers: It’s pretty big.

If we assume that the 1024 x 1024 pixel image is just an RGB with no alpha value, each pixel has \(256^{3}\) possible values. With two pixels, there are \(256^{2*3}\) possible numbers to describe all those images. For a 1024 x 1024 image, we get a total number of unique Babel Numbers:

\[\begin{aligned} (256)^{3 * 1024*1024} = 256^{3145728} \approxeq 7.76 * 10^{7575667} \end{aligned}\]It would be incredibly awkward if I got the maths wrong and had to rewrite a majority of the post…3

Anyways, we’ve done it. Every possible variation of every possible4 image is bounded under the finiteness of a simple, albeit HUGE number. \(7.76 * 10^{7575667}\) possible distinct images. This is an absurdly large number — it’s a 7 with 7.5 million zeros after it. A googol is only \(10^{100}\) — 100 zeros after a one, so our babel numbers can get really large (Although for some reason we know \(\pi\) to the 62.8th trillionth digit).

We should consider that, like the library of babel, most of these images convey nothing meaningful and are effectively gibberish to us humans, so the space of ‘useful images’5 is drastically lower. And if we did want to lower our resolution to 512 x 512, there would “only” be \(9.38 * 10^{1893916}\) unique images. I mean, it is about 5 million less zeros.6

Bringing Order to the Chaos

Right now, there’s no order to the numbers — we know that every image is attached to some unique Babel number, but we don’t know how the images are attached to the numbers — there’s no systematic ordering. So let’s do that.

- Let’s say Babel Number 0 goes to the image where every pixel in the screen is (0,0,0). It’s just a black image.

I’ve done the images as 512 x 512 but the same principles apply for any7 dimension.

I’ve done the images as 512 x 512 but the same principles apply for any7 dimension. -

Babel number 1 goes to the image where the first (top left) pixel is (1,0,0) and every other pixel on the image is (0,0,0)8. This is effectively the same image as the above, but with the first pixel having a slight red hue. I won’t show an image here since it looks almost exactly like the one above. Shocking.

- BN 255 has same as above, but its top left pixel is (255,0,0). This is a full black image but its first pixel is a pure red.

Can you see it? You’ll probably have to open the image up and zoom in to see that one tiny pixel.

Can you see it? You’ll probably have to open the image up and zoom in to see that one tiny pixel. -

BN 258 is (2, 1, 0) and everything else (0,0,0)

- And if I asked for a babel number of 3.924809e+115, we would get the following image:

Wonderful. We’re about 6 pixels in and approaching the total number of possible chess moves.

Wonderful. We’re about 6 pixels in and approaching the total number of possible chess moves.

Yeah, trawling through all these would take a long time. But seriously, this simple system contains everything. A good exercise for the reader would be to make an image -> Anti Babel number program. You could also try the converse: Babel number -> Image.

Once again, you could even convert videos into a sequence of babel numbers — they are, after all, just a series of images. Just… Don’t expect the playback time to be quick.

Calculating a Babel Number from an Image

Warning: (Minor) maths ahead.

To save you some thought, there’s quite a nice way to get the babel number from the RGB matrix of an image!

Behold: the dot product. All you have to do is flatten the matrix that composes an image into a 1D array, and multiply it by this “vector from hell” It is interesting how, the original RGB matrix is already a unique identifier (it literally describes the image after all), but to convert it to a lower dimensional number (like a scalar9), you have to do heinous acts to it — the higher dimensional structure seems to save on compute.

\[\begin{align} \text{Babel Number} &= \begin{bmatrix} 255 & 0 & 255 & 1 & 0 & ... & 0 \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 256^{0} \\ 256^{1} \\ 256^{2} \\ 256^{3} \\ ... \\ 256^{3(l*w)} \end{bmatrix} \end{align}\]This also gives us insight as to why the Babel numbers get so big: in a 512 x 512 image, we potentially have to multiply up to \(256^{3*512*512}\)!

Since every babel number is being multiplied by that forsaken vector, there might be some prime mathemagic one could do to reduce the computational cost of finding the corresponding babel number of an image whilst maintaining the uniqueness of all these identifiers, but I’m not sure how. I can sense ties to compression here10, but let’s just ignore this for now and continue our march.

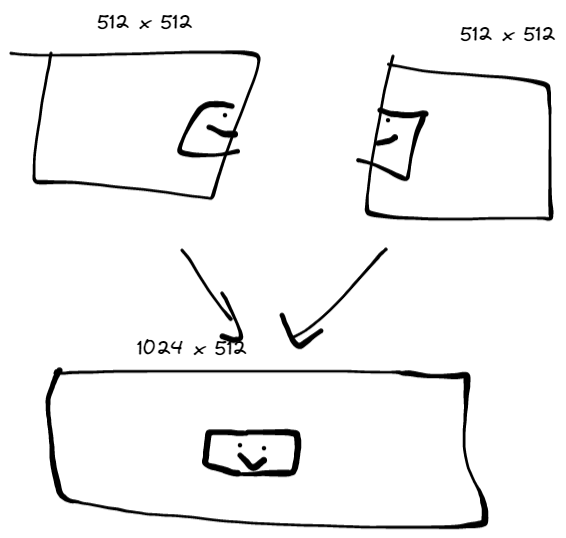

An interesting Idea I just came across in the shower — although these images are finite, you can combine two images with the babel numbers (for a given dimension) to make a larger image that wouldn’t be possible within the 512 x 512 system. What I mean by this:

- Imagine we have a camera and a room with a baby inside it. One babel number (512x512) would lead to the left half of the image — perhaps the carpet, some toys, a desk, a window. Another corresponding babel number must contain the right side of the room!! The side with the baby and the crib, to make a 512 x 1024 image.

Unfortunately, there must also be many possible images of the left and right — perhaps one of the left images has lovecraftian monsters waiting under the shadows, for instance.

Unfortunately, there must also be many possible images of the left and right — perhaps one of the left images has lovecraftian monsters waiting under the shadows, for instance.

Upon some further thought this is actually a very obvious conclusion. Consider a single pixel — with this, we can construct all possible images. It’s funny how sometimes you discover ideas in complex systems, but then these ideas can also be found in the simplest case. But it always feels like something more when you find it in the complicated system.11 This is still a pretty cool idea though — to make something 1024 x 1024 resolution, we just need four 512 x 512 images. That is, for every 4 babel numbers in the 512 size, we can generate a babel number for a 1024 size.

Now the great thing about this is that, if you’ve ever done anything in your life — public or private — you are caught! In 4K! Yes. You know what you did. Shame on you. I won’t share your secret with anyone, don’t worry!12

Now that we’ve gotten the maths out of the way, let’s head back to what this means.

What it means

Essentially, every possible image that you could imagine in your head can be described with a Babel Number. Maybe not its exact the resolution, but you can be damn sure the ideas of the image and what it represents are there. When you take a picture of a dog with your photo, you could think of it as searching through this Babel space of images to find the exact picture you took, before solidfying it and saving it to your device.

There’s your baby photos in there. A photo of your first birthday, with your family surrounding you — even if nobody took that photo.

One of those pictures will have your date of death on it. It will have a picture of your funeral, along with all its attendants.

Another will have how you died, the moments before, the moments after. Perhaps you fell down stairs — it will have it. At this resolution, another combination will have the picture of your death, and a good written summary of how you died right below. And that summary? There’s a picture written in every known human language.

Actually, it’s not just one photo. It’s an entire set. Take for instance, the babel number that’d lead to an image of your birth from a bird’s eye view. Now, we can have 1 pixel off, and you would still be able to easily discern it as your birth, yes? So realistically, we have at least 1024 * 1024 images that have your birth on it, within a one pixel accuracy.There’d be a gray scale version of that image too, of course. And another one, half gray scale and half coloured.

All those combinations. Just for you.

Your most private moments, right there, for anyone to see, if they could only search through the combination space. One click of a button, one little randomisation to a babel number. And you appear — staring right back at yourself.

Any private thoughts that could be written within the image — right there. Any mathematical proofs that could fit on it — it’s in there.

There could be things that would scar you for life, or things that would bring you immense joy.

If you had the right numbers, from one possibility to the next, you could attach the images into a fully comprehensive documentary of your life.

Your past.

Your present.

Your future.

It’s all there. Just waiting.

IN 4K!

Yes, infinity is cool.

But, do not underestimate the power of the finite.

Author’s Notes:

So, I created the document for this post on April 11th, and it was mainly just the idea and the emotional OOMPH you had at the end — string the top bit of the introduction, and everything under “What it means”.

However, when I revisited this in late June, I added the Babel numbers. I’m not sure how this impacts the flow / if this mix between math and existential oomph is jarring, so feedback is appreciated! And then of course, the Incident of Powers that shall not be named happened…

-

Although there seems to be an image thing on the site too… Is it seriously just impossible to come across a unique idea? Damn! Any idea you come up with, search long enough and someone else has done it before. ↩

-

But. Y’know. Without all the groundbreaking relevations and game-changing ideas that shook the foundations of mathematics. Yeah, maybe just call it a Babel Number. ↩

-

Let’s just not talk about it. ↩

-

1024 x 1024, but it can be extended to any dimensions. ↩

-

Images that actually tell us something — like a dog, or a cat, or a CCTV snapshot of a person at a gas station counter late at night. ↩

-

Which is still about, hmm, 1.8 million zeros more than the estimated number of atoms in the universe. ↩

-

Positive natural dimension… Seriously? You want to nitpick here? ↩

-

Before, I actually had it like Babel # 1 goes to all pixels (0,0,0) except for the bottom right pixel, which would be (0,0,1). I decided to flip it just because it’s more intuitive for the number to “fill up” the pixels, and potentially a bit easier to code for as well. ↩

-

Just a number with no structure, like 3 degrees Celsius. There is no direction. A vector has direction — like 5 Newtons north. ↩

-

And maybe hashing? It’s almost like computer science is not just about computers — it’s about information — and not specifically the little devices in front of us. There’s even a hint of entropy — likely configurations vs unlikely configurations! ↩

-

Before slapping yourself in the face when you realise it’s not an emergent property, and could’ve been found much more easily. This happens a lot to me, for some reason. So silly! ↩

-

Because you aren’t actually speaking to me. You’re reading a blog. Are you alright? Do you need to drink some water, maybe lay down? Rest well, friend. You need it to live. ↩