Reflecting Rays, Circular Mirrors and Points

The Original Question

Imagine a circular mirror with a radius of 5 that exists on an origin.

A ray of light beings at 10i-10j and enters the mirror such that

it intersects the point (-2, sqrt(21)).

Assume that the mirror allows a ray to enter before closing and thus trapping a light ray inside.

What is the point where the first reflected ray

collides with the circular mirror (excluding the reflected ray's initial position)?

This is a calculator allowed question (I’m thinking of a TI-84 graphics calculator when I say this) Note on original question. 1

Table of Contents

- The Original Question

- Preface

- Solving

Preface

I had the idea for this question just after my final internal specialist exam (specialist is equivalent to Maths C or whatever your extended x2 maths is). However, this question isn’t really a specialist question as much as a question that involves some topics covered in the subject. I implore you to try it out! You can use google, but try to search for sub-problems instead of the true problem instead.

This question actually has some old roots in a problem I was thinking about in 2019 – ray reflection –. There’s a quick conclusion I wrote somewhere: I’ll upload some pictures if I can find the papers.

Anyways, let’s delve into this one! Don’t ask me why, but this question brings me joy: Easy to understand and interpret yet relies on execution or ‘elegance’ to achieve. If you figured out a different / better way of solving it, please tell me on one of my contacts!

The way I will solve it is by actually explaining the concepts before using them, which is useful for learning but takes much more space.

Solving

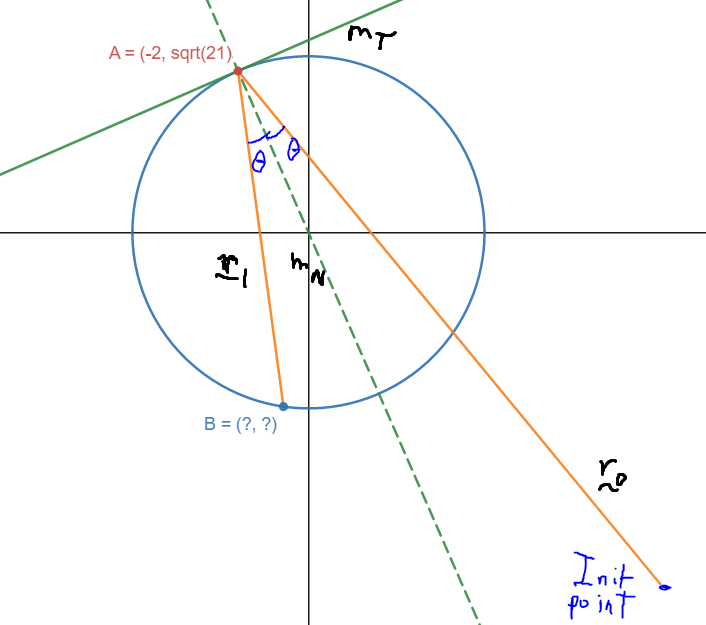

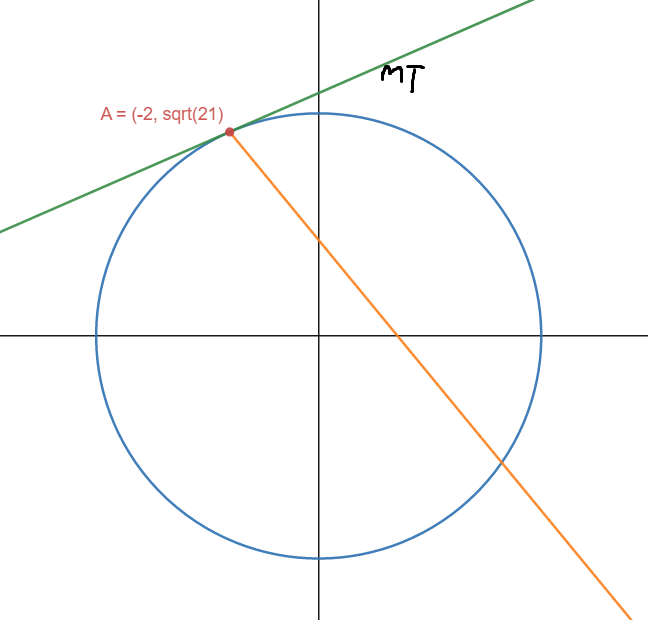

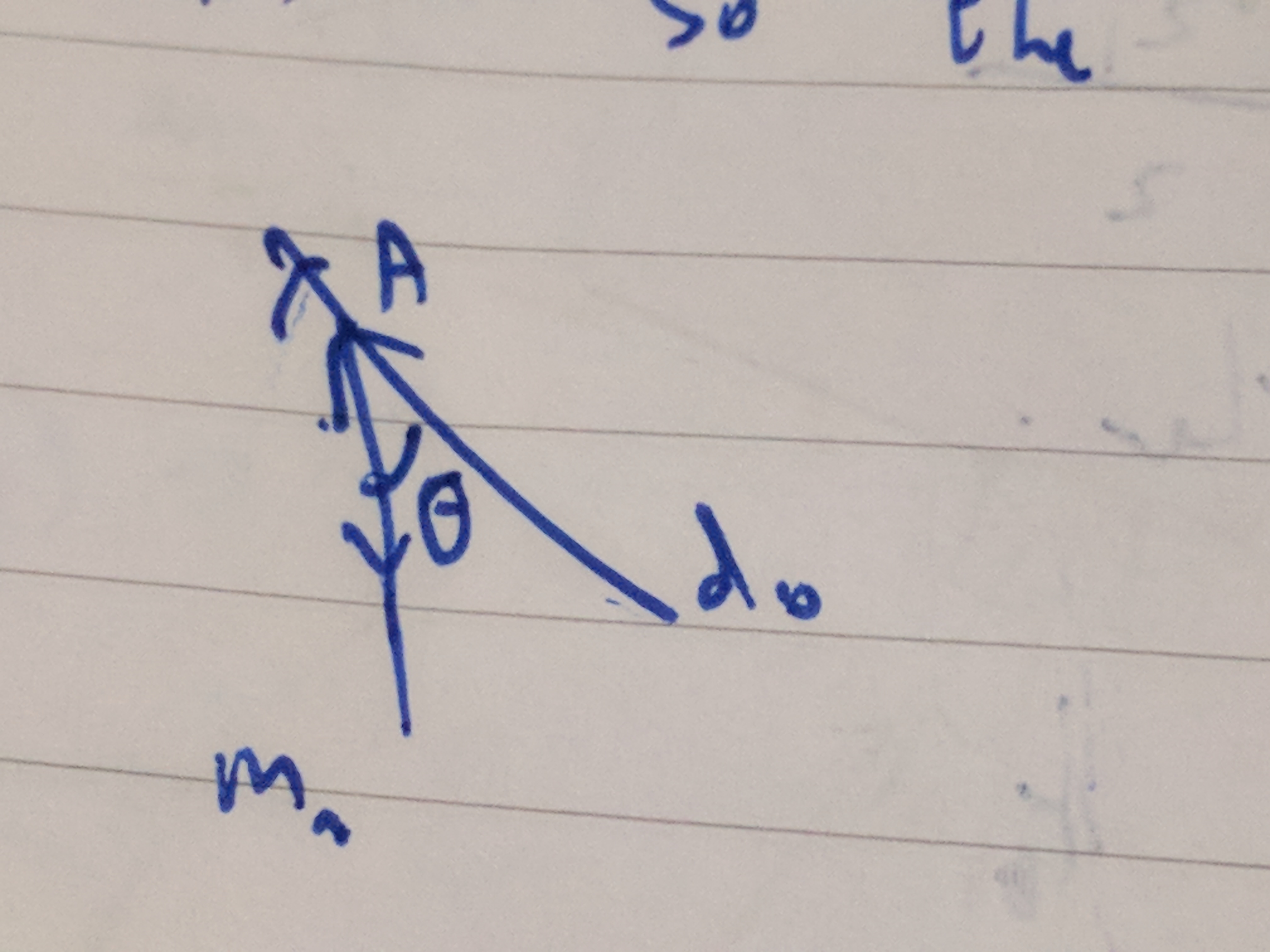

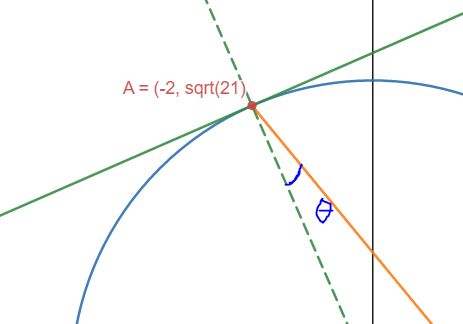

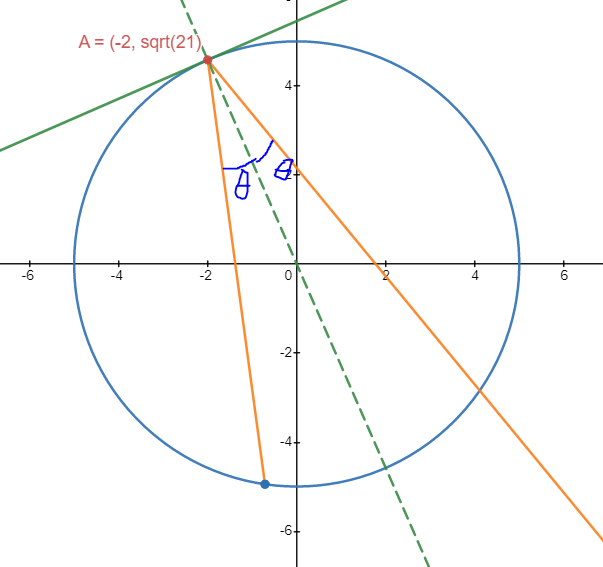

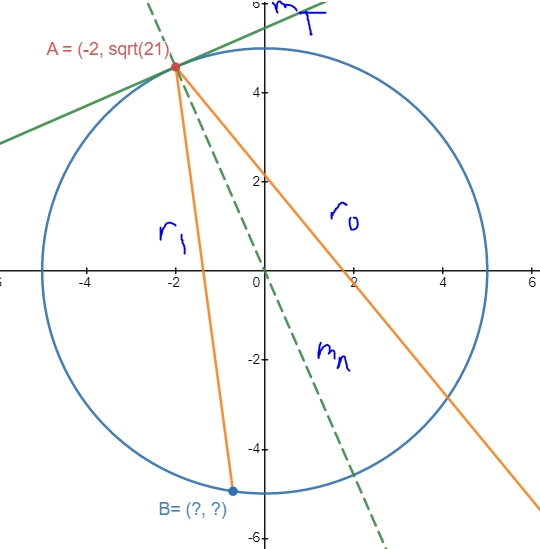

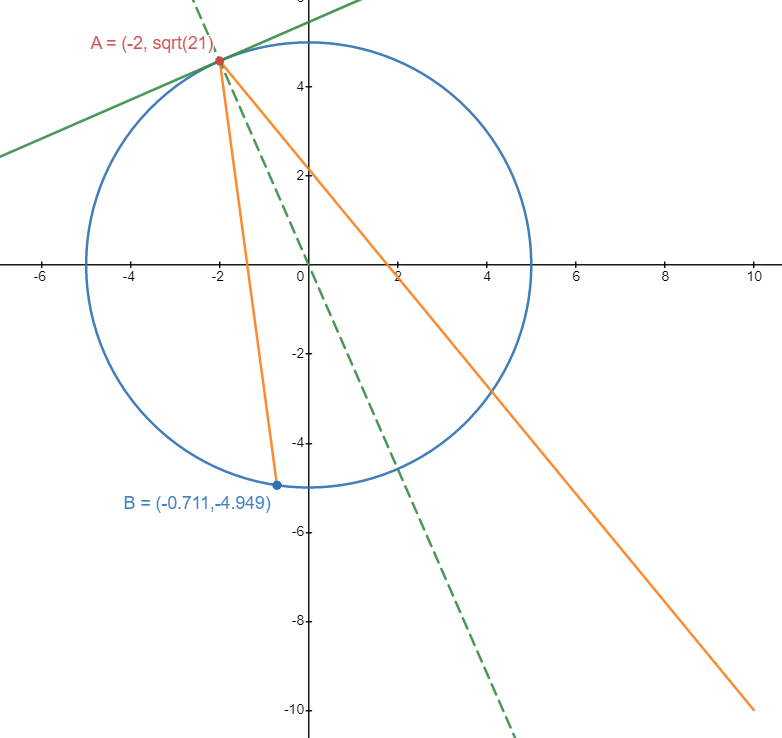

Firstly, let’s understand what’s actually going on here by drawing a nice diagram. I’m going to be using desmos here with some very nice snipping tool skills (it was either that or my hand-drawn items).

Now we know what’s actually going on.

Firstly, there’s the light ray \(r_0\) which enters the mirror (imagine there’s a hole that closes once the light enters) and collides with the circular mirror at Point A \((-2, \sqrt21)\). It is then reflected by some \(\theta\) and the first reflected ray \(r_1\) collides with the mirror at Point B, which is what we’re trying to find. We are solving for Point B.

From the question (and the law of reflection), we know that \(r_0\) reflects with some \(\theta\) with respect to the normal \(m_n\). But how can we find it? Well, if we can somehow find the tangent \(m_T\) at Point A, we’ll be able to find \(m_n\).

We can get to Point B and figure out the solution in a few simple steps. Working backwards, we need \(r_1\) so we want to somehow create a new vector \(\theta\) away from \(m_n\). We can work out \(\theta\) with \(m_n\) and \(r_0\). We can get \(m_n\) with the tangent and \(r_0\) is relatively easy to find. Thus:

The steps

1. Find the direction vector of \(r_0\) (i.e so it collides with A from the initial point).

2. Find the tangent @ Point A

3. Get to the chopper normal (\(\frac{-1}{m_T}\))

4. Find \(\theta\)

5. Generate the reflected ray \(r_1\)

6. Find the reflected ray’s intersection with the circle => Point B.

I made some calculation errors on some steps, but Step 5 was the one that stumped me for a bit when I was trying to solve it; kept gettin nonsense \(r_1\)’s. Anyways, let’s solve it.

1. Find the direction vector of \(r_0\)

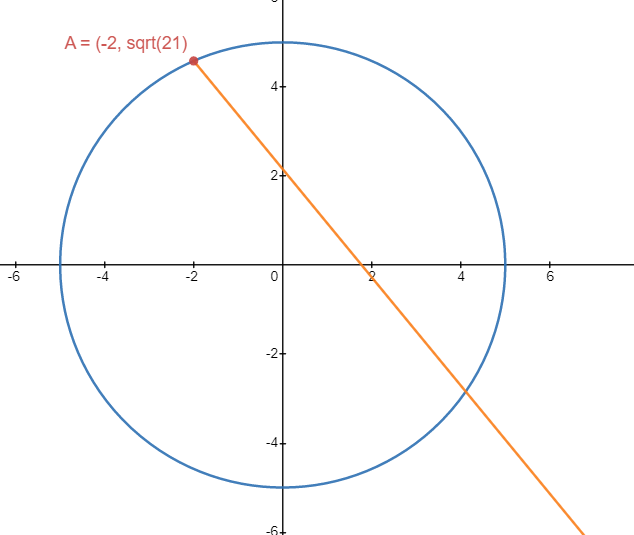

Let’s get the diagram back.

\(r_0\) being in i,j components is not really ideal, and in this case we want (x,y). So we’ll just convert it. The ray starts at \((10, -10)\) and we have to reach \((-2, \sqrt21)\).

Well, let’s get the ray equation \(\vec{r} = \vec{a} + k\vec{d}\).

\(\vec{a}\) is the initial position, \(\vec{d}\) is the direction vector, k is a constant that changes the length of the ray. We don’t really care about k here.

Of course, the direction vector is the direction it’s going: towards Point A, \((-2, \sqrt21)\) from \((10, -10)\). Thus, the direction is just:

I was going to do the calculations in column vector form but we’re going to stick with i,j notation right now because it’s easier to type up. I might switch it over eventually. Maybe. Probably not.

So it’s going backwards in x, upwards in y. Makes sense to me! Note: it doesn’t matter if \(\vec{d}\) is \(-12i+(\sqrt21 +10)j\) or \(-120i+(10\sqrt21 +100)j\), they still point in the same direction (e.g <–, <—-) (same gradient). They just have different lengths; k is the scaling factor.

So:

\(\vec{r} = \begin{pmatrix} 10 \\ -10 \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} -12 \\ \sqrt21 + 10 \end{pmatrix}k\)

Cool.

We already know it hits at Point A, so now let’s find the normal! But first, we need to find the tangent as an intermediary step.

2. Find the Tangent at Point A

I’m going to assume you have knowledge of derivatives & implicit differnetiation here (sorry). Now, a derivative is literally just a ‘gradient function’. Instead of doing annoying \(\frac{\delta y}{\delta x}\) every time, we do a sneaky calculus and say 2 points reaching infinitesimaly close at Point X have gradient \(m = f'(x)\). 3blue1brown has good animations of these.

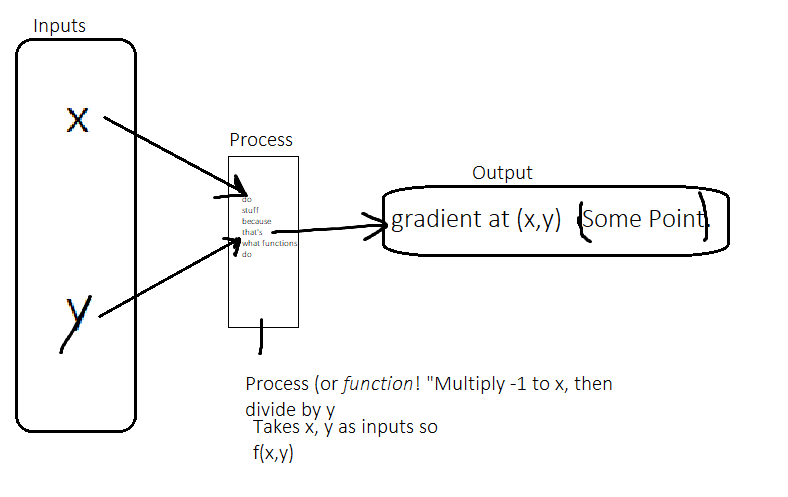

Thus, a derivative simply maps a point -> gradient.

Using implicit differentiation, the derivative at Point A is just:

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{d}{dx} (x^2 + y^2) &= \frac{d}{dx} 5^2 \\ 2x + 2y\frac{dy}{dx} &= 0 \\ \frac{dy}{dx} &= \frac{-x}{y} \end{aligned}\]Note that unlike the simple derivatives, you have both x and y to input to get the gradient. I.e, it’s not \(f(x)\) but \(f(x,y)\). Specifically: \(f(x,y) = x^2 + y^2 = 5^2\)

\[f'(x,y) = \frac{-x}{y} = \frac{dy}{dx}\]

Thus, for Point A \((-2, \sqrt21)\):

\[\begin{aligned} f'(x,y) &= f'(-2, \sqrt21) \\ m_T &= -\frac{2}{\sqrt21} \end{aligned}\]We’ll call it \(m_T\) as a nickname for ‘tangent gradient’.

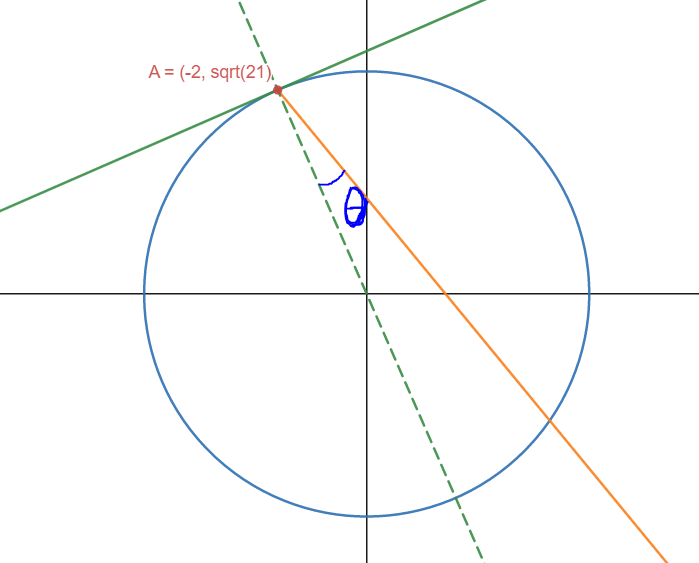

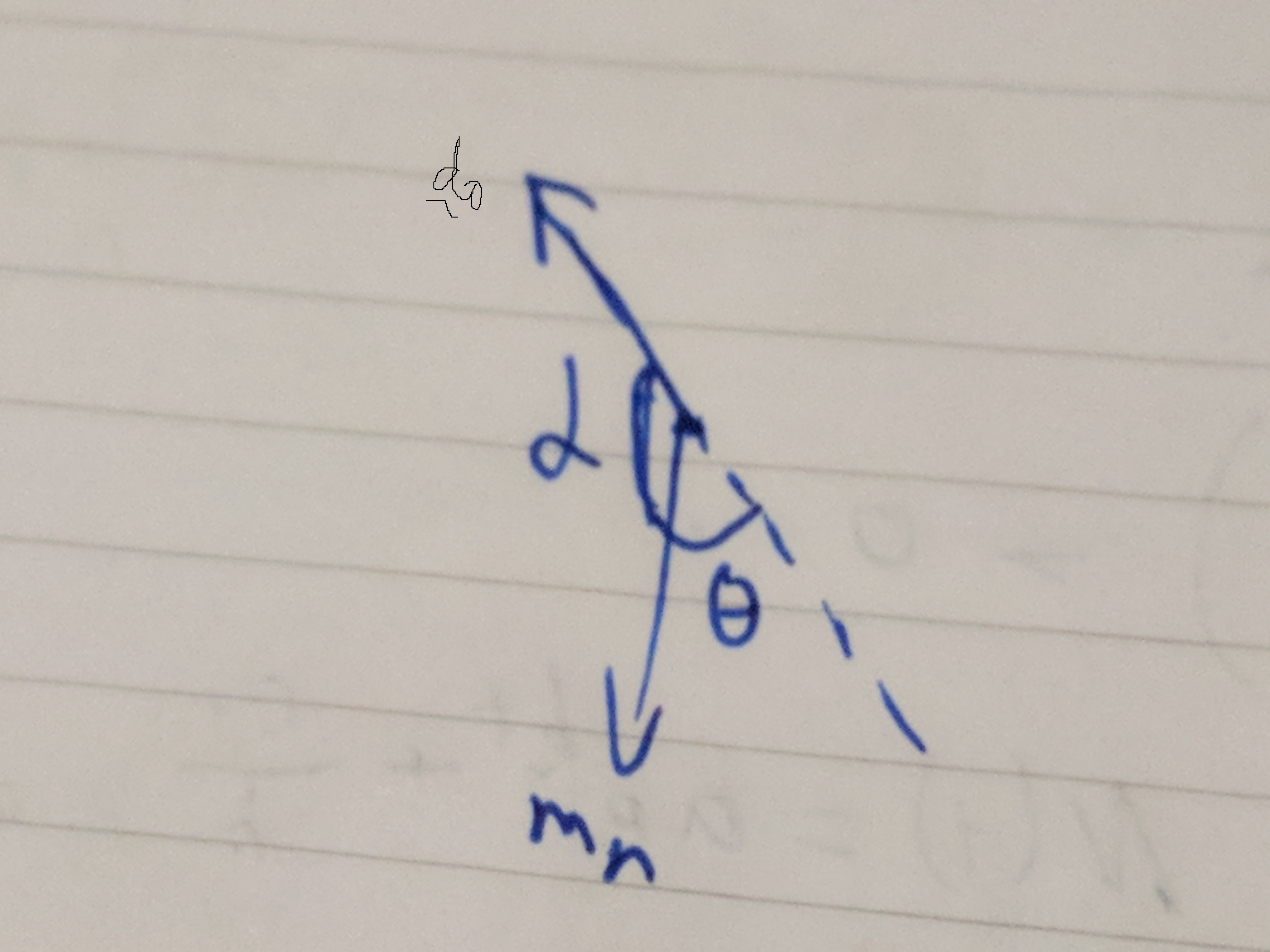

Now, our diagram looks like this:

3. Find the normal

Easiest one. Just flip it \(90^o\). There’s a few ways to know that \(m_n = \frac{-1}{m_T}\), and I actually only know one of them (figured it out when writing the post, actually!) If you assume knowledge of the dot product \(a \cdot b\), and know that when \(a \cdot b = 0\), a is perpendicular to b => \(a \perp b\). And really, the \(\frac{-1}{m_T}\) is flipping the tangent, and then making it -1/x so that when you dot product them they become 0. Thus, they are perpendicular! Cool. So,

\[\begin{aligned} m_n = \frac{-1}{m_T} &= \frac{-1}{\frac{2}{\sqrt21}} \\ m_n &= \frac{-\sqrt21}{2} \end{aligned}\]Oh yeah, our diagram’s coming together (no meme images today, however).

I can’t help but draw the next thing here: humans have foresight, we can plan, so use it! We’ll cal the first reflected ray \(r_1\).

4. find \(\theta\)

How can we find \(\theta\)? Well..

Dot product!

\[\vec{a} \cdot \vec{b} = |a||b|cos(\theta)\]But our \(m_n\) is in cartesian form and not vector, oh noes! Is there a way to convert a gradient into a direction vector? 🤔

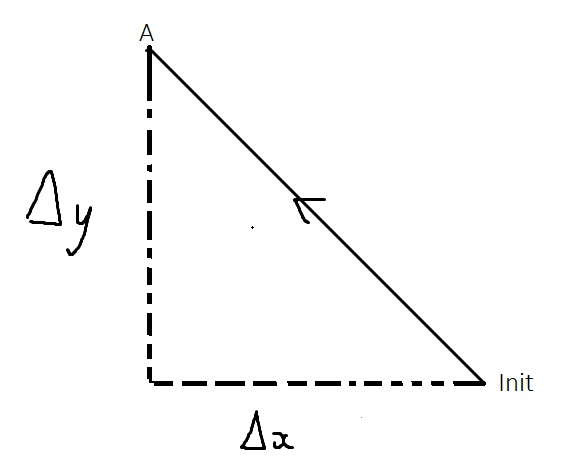

Well, if a gradient is in \(m = \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\) and \(\vec{d} = \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix}\) and our \(m_n = \frac{-sqrt21}{2} = \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\)… HMMMMM.

See where I’m going?

Flip the lil thingy!

\[\begin{aligned} m_n &\to \vec{d} \\ \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} &\to \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix} \\ \frac{-\sqrt21}{2} &\to \begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ -\sqrt21 \end{pmatrix} = \vec{d_n} \\ Dn deez NU- \end{aligned}\]I’m just gonna call it \(m_n\) even though it’s technically \(\vec{d_n}\). Take it or leave it. So now we have our \(m_n = \begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ -\sqrt21 \end{pmatrix}\), going right an down. \(\vec{d_0} goes \begin{pmatrix} -12 \\ \sqrt21 + 10 \end{pmatrix}\) so the diagram looks like:

So, doing \(\begin{aligned} \vec{a} \cdot \vec{b} &= |a||b|cos(\theta) \\ \theta &= \cos^-1(\frac{a \cdot b}{|a||b|}) \end{aligned}\)

We’re finding the angle between vectors, right, so let’s just do it!

Wooahh! Slow down there Nelly, what are you actually calculating?

In the formula above, \(\theta\) is the angle between 2 vectors.

See anything fishy with the diagram above? Let’s try to make A the origin, and since they’re direction vectors, it doesn’t matter where they start as long as they meet. They’ll always give the same angle (draw this and experiment on paper to proof it for yourself if you want).

See it? Our \(\theta\) isn’t actually what’s being calculated! We’re really calculating \(\sim\)!!! Since that’s the angle between the two direction vectors.

Let’s try it. Calculate \(\theta\).

Seriously, use \(\vec{a} = m_n = \begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ -\sqrt21 \end{pmatrix}\) and \(\vec{b} = \vec{d_0} = \begin{pmatrix} -12 \\ \sqrt21+10 \end{pmatrix}\).

I get \(\theta = 164.13^{\circ}\). You can use symbolab , which seems a bit nonsense when we look at the diagram [show diagram small] and especially the desmos diagram for exact numbers.

Does that look like \(164^{\circ}\) to you?

Basically, what we thought was \(\theta\) in our heads wasn’t actually the real \(\theta\) we were calculating.

So, how do we fix it? Well, it’s actually really easy.

If that vector gets us the \(\propto\), then if we turn \(\vec{d_0}\) around (direction vector of the first ray), it should give use the other angle.

If that vector gets us the \(\propto\), then if we turn \(\vec{d_0}\) around (direction vector of the first ray), it should give use the other angle.

So, \(-\vec{d_0} = \begin{pmatrix} 12 \\ -\sqrt21-10 \end{pmatrix}\), and now we get:

Tada! And let’s try it with our angle formula,

\(m_n = \begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ -\sqrt21 \end{pmatrix}\) and \(-\vec{d_0} = \begin{pmatrix} 12 \\ -\sqrt21-10 \end{pmatrix}\)

\[\begin{aligned} \theta &= \cos^-1(\frac{a \cdot b}{|a||b|}) \\ &= \cos^-1(\frac{\begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ -\sqrt21 \end{pmatrix} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 12 \\ -\sqrt21-10 \end{pmatrix}}{|m_n||-\vec{d_0}|}) \\ &= \cos^-1(\frac{2*12 + -\sqrt21*(-\sqrt21-10)}{5*\sqrt{265+20\sqrt{21}}}) \\ &= \cos^-1(\frac{90.826}{83.15}) \\ &= \cos^-1(0.96187) \\ \theta &= 15.873^{\circ} \end{aligned}\]Now we know the angle that the ray also gets reflected by! If you calculated the other angle before, you’ll notice that our \(\theta\) is just \(180^{\circ}-original\). If you don’t get why, draw out the 2 vectors. Seriously! And then try flipping one of them and seeing what angle that gets. Straight lines, 180… Ring a bell?

5. Generate the reflected ray \(\vec{r_1}\)

We’ll say the initial point \(\vec{a} = \begin{pmatrix} -2 \\ \sqrt21 \end{pmatrix}\) so it begins there. From the info we have, how do we figure out \(\vec{r_1}\), namely, its direction vector \(\vec{d_1}\)?

Well.

This took a while, but first I tried to rearrange dot product maybe? But that didn’t make too much sense to me. Why’s the vector down there??

Let’s simplify the problem: Given an angle and a vector, how do I produce another vector \(r_1\) (the rotated vector)?

Eventually, I found rotation matrices! They’re so good. Here’s a link to read more, and this one

\[R(\theta) = \begin{bmatrix} \cos{\theta} & -\sin{\theta} \\ \sin{\theta} & \cos{\theta} \end{bmatrix}\]Basically, multiplying a vector \(v_1\) and \(R(\theta)\), we do:

where \(x' = x\cos{\theta}-y\sin{\theta}\),

and \(y' = x\sin{\theta} + y\cos{\theta}\)

These are OP. We can use either \(m_n\) and rotate clockwise by \(\theta\) or use \(-\vec{d_0}\) and rotate clockwise by \(2\theta\). By the way, rotating clockwise is literally just a \(-\theta\).

We’ll just use \(m_n\).

\[\begin{aligned} \vec{d_1} &= R(\theta) \cdot \vec{m_n} \\ &= R(-15.873^{\circ}) \cdot \vec{m_n} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} \cos{-15.873^{\circ}} & -\sin{-15.873^{\circ}} \\ \sin{-15.873^{\circ}} & \cos{-15.873^{\circ}} \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ -\sqrt21 \end{pmatrix} \\ \vec{d_1} &= \begin{pmatrix} 0.670 \\ -4.955 \end{pmatrix} \end{aligned}\]Note: You might get a different answer, but they should still be the same direction vector (i.e one is a scalar of the other). You can easily check this by doing \(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\) on desmos or something and seeing if both our vectors give you the same gradient. Don’t forget your angle changes based on which vector you rotated :).

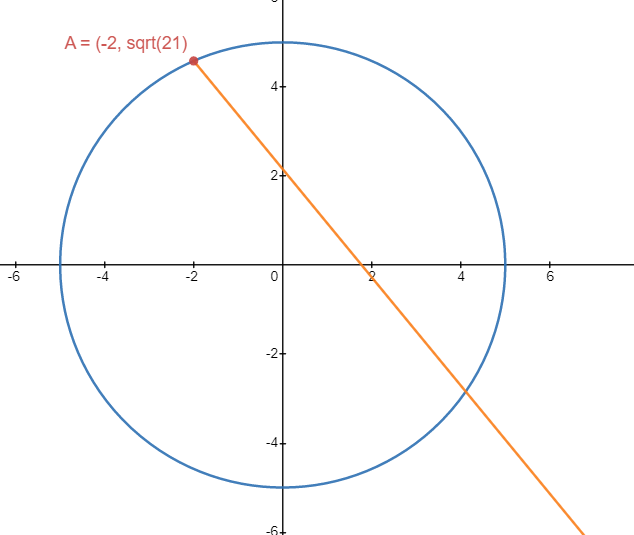

Nice! And since we know its starting point Point A \((-2, \sqrt21)\):

\[\begin{aligned} \vec{r_1} &= \vec{a} + k\vec{d} \\ \vec{r_1} &= \begin{pmatrix} -2 \\ \sqrt21 \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} 0.670 \\ -4.955 \end{pmatrix}k \end{aligned}\]And that’s our reflected ray equation!

6. Find Point B

This one is arguably very simple (especially if you have technology). You just find where the ray and the circle intersect. There’ll only be two points (think of a straight line going through a circle), and one of them is our initial starting point.

The only confusing part would be converting from vector format to cartesian form so you can figure out the intersection, but as long as you just think about what’s going on, and what’s what, you’ll be fine. Let’s get converting!

Alright, we have: 1 point (our initial point), and the direction (i.e our gradient). As I said earlier on, vector is in \((x,y)\) but gradients are \(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\) so we just flip our \(\vec{d_1}\) from \(\begin{pmatrix}0.670 \\ -4.955 \end{pmatrix}\) to \(m = \frac{-4.955}{0.670}\). That’s our gradient (you can see it in desmos; it’s going downwards. Makes sense to me!) Our initial point is \(-2i + \sqrt21j\), so, using a nice form of straight line equation that lets us find it given a specific point:

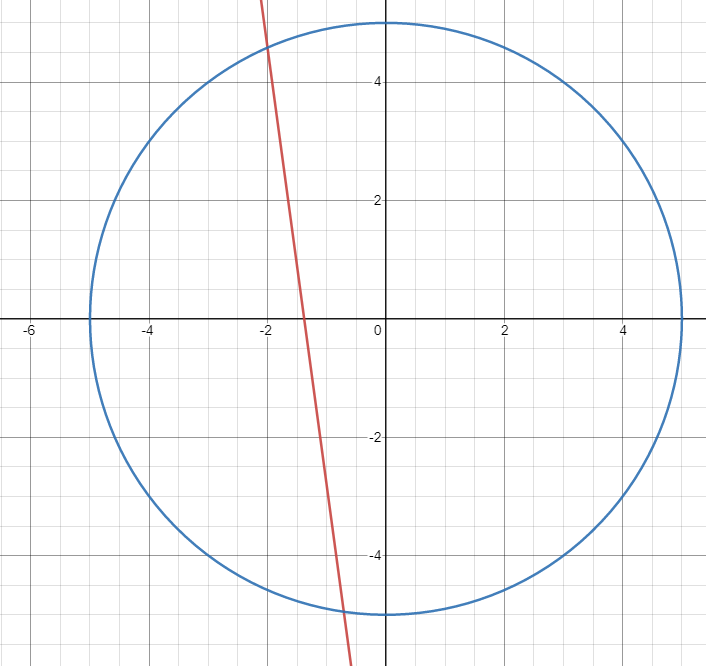

\[\begin{aligned} y - y_1 &= m(x-x_1) \\ y - \sqrt21 &= \frac{-4.955}{0.670}(x--2) \\ y ~&= \frac{-4.955}{0.670}x -14.791 +\sqrt21 \\ y ~&= \frac{-4.955}{0.670}x - 10.208 \end{aligned}\]Looking at an desmos image, it looks like.

But isolation is sad! (And dangerous), so let’s see our final image.

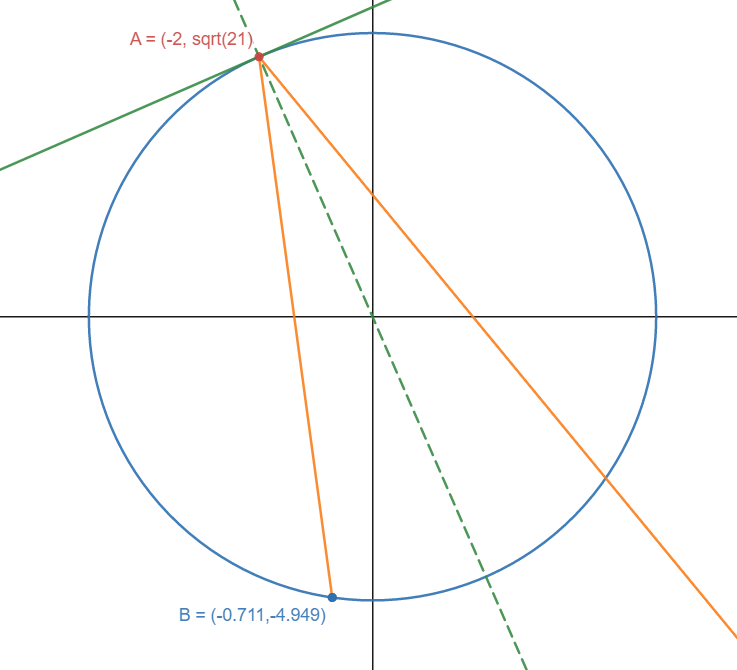

With axes shown:

Our Point B is approximately \((-0.711, -4.949)\)!!! Woooo!!!

The way you solve it on paper is to substitute y into \(x^2 + y^2 = 25\) and and solve that quadratic. So, for solving on paper:

\[\begin{aligned} x^2 + (\frac{-4.955}{0.670}x - 10.208)^2 &= 5^2 \\ 55.69x^2+150.99x+79.2 &= 0 \\ x &= -2, -0.711 \\ \end{aligned}\]So there’s our 2 intersection x’s, and we know that \(x = -2\) is our initial point, so the answer must be \(x = -0.711\). Don’t just end it here, finish the question! Find Point B!

\[\begin{aligned} x^2 + y^2 &= 25 \\ y &= \sqrt{25-(-0.711)^2} \\ y &= \pm 4.949 \end{aligned}\]Using some common sense, the sector of the circle we want is in the negative y axis, so it’s \(y =-4.949\). Therefore, our \(Point B = (-0.711, -4.949)\). Nice!

Extensions

The first way that comes to my mind is: Well, if you can do it for 2D circles, why not 3D spheres? Differentiating it (I’m guessing by using multivariable calculus, which I have not currently learnt) to get a plane equation tangent @ any point on the sphere, and doing the same thing (but in 3D) of course would be interesting. And well… Why stop there!? An N dimensional hypersphere, why not? It’ll still bounce at the same angle incoming to the normal (normal hyperplane?). :o

The second extension would be to generalise this problem into f(n) \rightarrow (x,y). I.e, given how many bounces you want (n), tell me the Point that the light ray hits. This is why I started the ray as \(r_0\), so you could easily say: “Oh, where does the 5th reflected ray hit? f(5). The question we solved above is f(1), “The point that the first reflected ray hits”, Point B.

I’d probably work this out programmatically first before trying to convert it back into maths speak.

The second extension would be to generalise this problem into f(n) \rightarrow (x,y). I.e, given how many bounces you want (n), tell me the Point that the light ray hits. This is why I started the ray as \(r_0\), so you could easily say: “Oh, where does the 5th reflected ray hit? f(5). The question we solved above is f(1), “The point that the first reflected ray hits”, Point B.

I’d probably work this out programmatically first before trying to convert it back into maths speak.

If you combine the two extensions I suggested, the ultimate question would be,

“Create an \(f(D, n, \vec{a}, \vec{d}) \rightarrow (x,y,z, ...)\) that returns the coordinates of the light ray \(\vec{r_n}\) collision within a hypersphere at Point \(P_n\) given the dimensional number of the system, \(D\), the number of times the ray is reflected, \(n\), and the initial starting point and direction vector of the light ray \(\vec{a}, \vec{d}\) respectively. Assume the light can enter the hypersphere before it is trapped inside. Let \(\vec{r_0}\) be the initial ray.”

It’s worded a bit poorly, but you’d get what I meant given the context of this post. For context, our Point A in the 2D example would be considered \(P_0\), and Point B (the one we solved for) would be \(P_1\). That sounds fun. Actually, you could generalise it even more by just letting \(P_1\) become \(P\), any point on the hypersphere. Contact me if you do them, I’d love to see it! I wonder if it eventually hits all points on the hypersphere or if it follows a pattern, and whether this applies to any dimension or only certain ones. So cool, right?

Furthermore, if you really felt like it, you could add irl values like the speed of light so \(\vec{r}\) becomes a function of time \(\vec{r}(t)\). From there, you could ask “When does \(P_n\) occur if the first ray is initialised at t=0 seconds?”

Footnotes / Other

If you look back in history, this problem actually has some ancestry roots in a problem I was thinking about in grade 10 involving the reflection of light in a mirror took me way too long to notice the simplest thing - I blame missing a lesson + only being taught a ‘fixed’ set of cases instead of the general system). Huh!

https://matthew-brett.github.io/teaching/rotation_2d.html https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rotation_matrix https://www.wolframalpha.com/widgets/view.jsp?id=bd71841fce4a834c804930bd48e7b6cf

-

Originally, the question was -10i-10j and point -2, -sqrt(29). There’s a few errors with this (I had the wrong diagram in my head which caused me to get the wrong angle and be thoroughly confused for an hour or two until it clicked): 1) The point that the ray intersects is actually on the same side as the ray initialisation point, i.e it ‘hits’ the circle on the outside (which I then demand it to bounce off). I.e it never got inside. Lmao. ↩